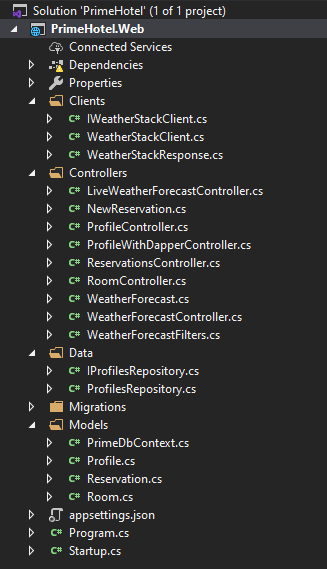

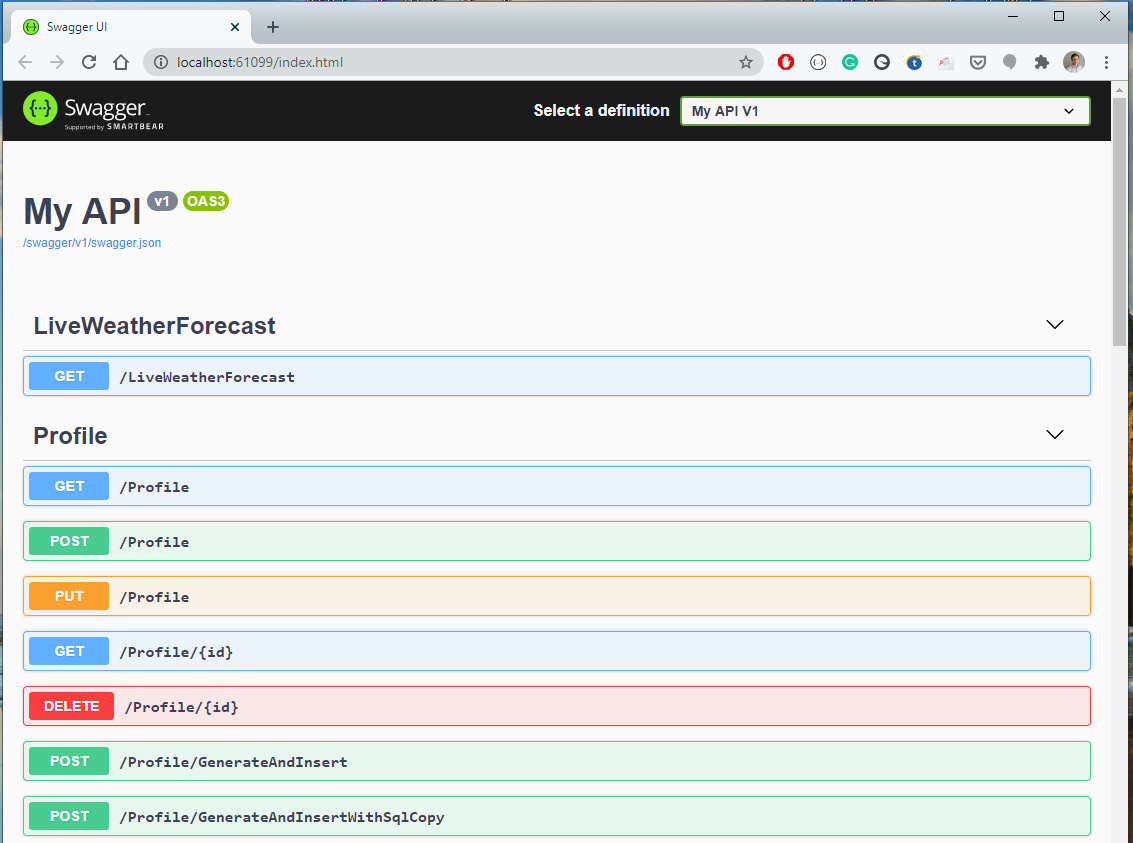

Sending a request in ASP.NET Core in .NET 5 is a standard operation that can be achieved pretty easily. However, details matter in this case and I’ll show you the best practice available. We will also take a look at some advanced features to get the full scope.

Using a real available API

In this article, I will be using 3rd party free service for fetching weather forecasts – http://weatherstack.com. To be able to use it, just register on their website and you can use it as well. 1000 requests in a month are available for a free account and that should be more than enough to fulfill our needs.

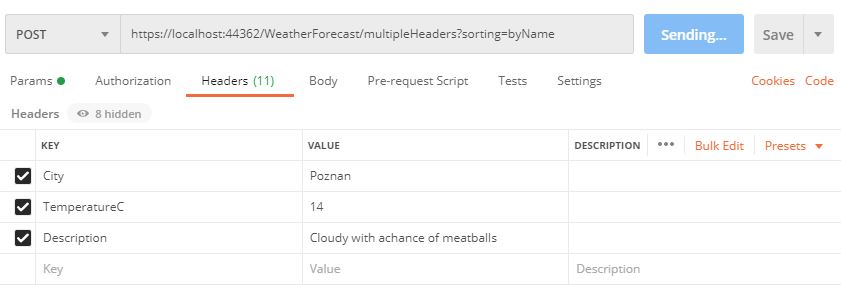

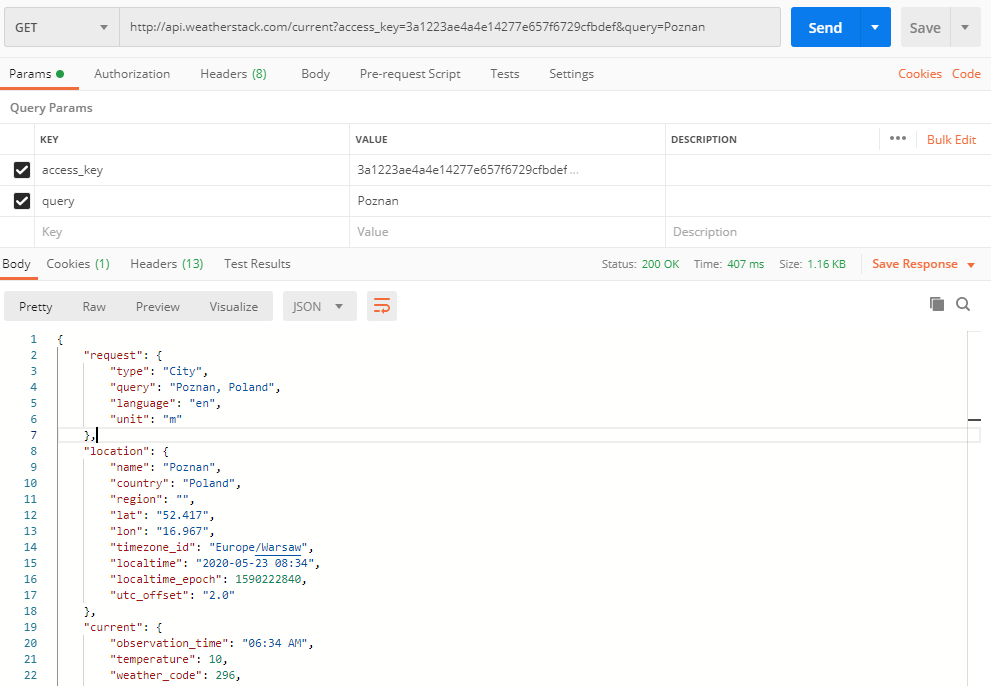

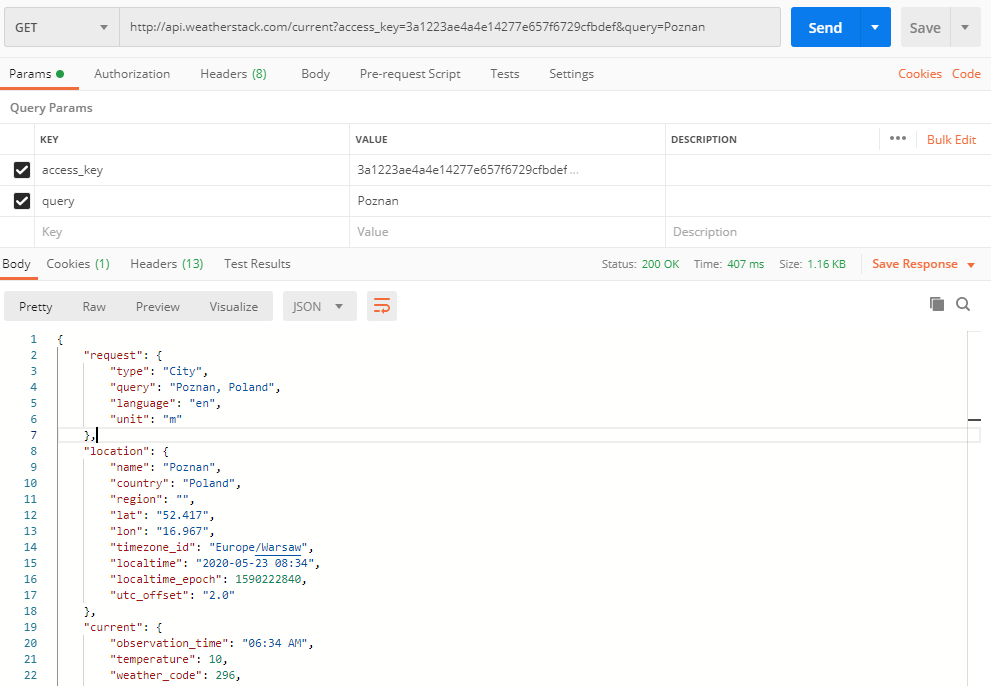

First, let’s have a look at the requests we are going to make. To test the API, I’m using a Postman app, which is very powerful, yet intuitive. I strongly encourage you to read my article about it here: Postman the right way

Here is how a request to fetch current weather in Poznań looks like:

This is a GET request to http://api.weatherstack.com/current with two parameters:

access_key which you get when registering on the websitequery that can be a city name

The response that we got is a 200 OK with JSON content.

To make this request, I’ll create a WeatherStackClient class.

using Microsoft.Extensions.Logging;

using System;

using System.Net.Http;

using System.Text.Json;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

namespace PrimeHotel.Web.Clients

{

public class WeatherStackClient : IWeatherStackClient

{

private const string AccessKey = "3a1223ae4a4e14277e657f6729cfbdef";

private const string WeatherStackUrl = "http://api.weatherstack.com/current";

private HttpClient _client;

private readonly ILogger<WeatherStackClient> _logger;

public WeatherStackClient(HttpClient client, ILogger<WeatherStackClient> logger)

{

_client = client;

_logger = logger;

}

}

}

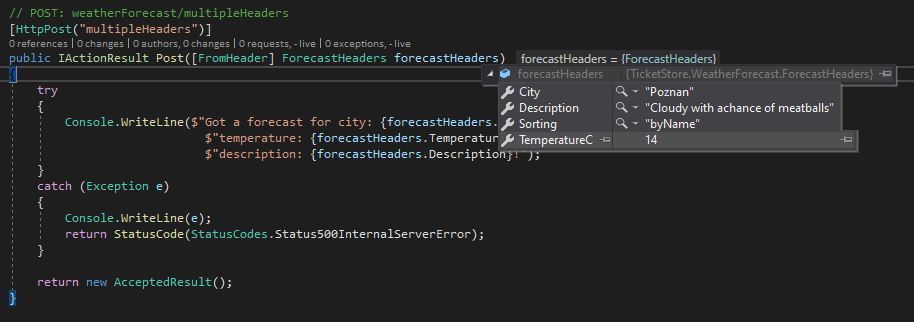

There are a few things to notice here:

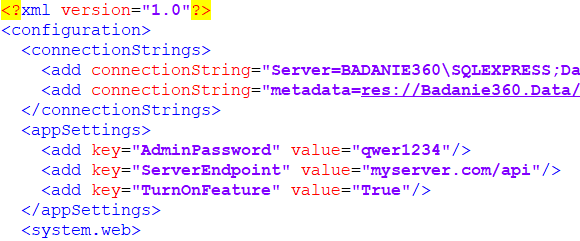

AccessKey which is hardcoded for now, but in a real-life API should be moved to configurationIWeatherStackClient interface that is introduced for Dependency Injection supportHttpClient class is passed in a constructor. It will be automatically created and maintained by the framework

Now let’s create the logic.

public async Task<WeatherStackResponse> GetCurrentWeather(string city)

{

try

{

using var responseStream = await _client.GetStreamAsync(GetWeatherStackUrl(city));

var currentForecast = await JsonSerializer.DeserializeAsync<WeatherStackResponse>(responseStream);

return currentForecast;

}

catch (Exception e)

{

_logger.LogError(e, $"Something went wrong when calling WeatherStack.com");

return null;

}

}

private string GetWeatherStackUrl(string city)

{

return WeatherStackUrl + "?"

+ "access_key=" + AccessKey

+ "&query=" + city;

}

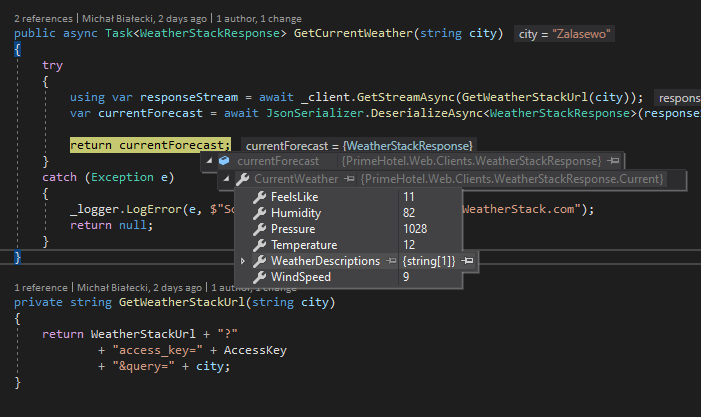

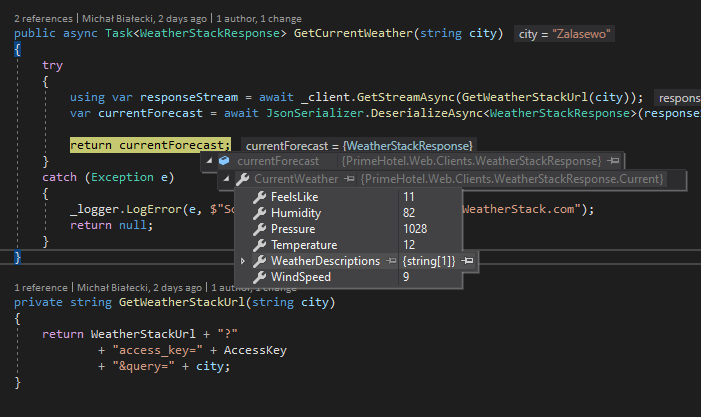

Let’s go through this code and explain what’s going on:

_client.GetStreamAsync is an asynchronous method that takes a URL an returns a stream. There are more methods, like: GetAsync, PostAsync, PutAsync, PatchAsync, DeleteAsync for all CRUD operations. There is also GetStringAsync that serializes a response content to string – just like GetStreamAsync doesGetWeatherStackUrl is merging a service URL with query parameters, returning a full URL addressJsonSerializer.DeserializeAsync<WeatherStackResponse>(responseStream) deserializes a stream and format output as a WeatherStackResponse class

The WeatherStackResponse class looks like this:

using System.Text.Json.Serialization;

namespace PrimeHotel.Web.Clients

{

public class WeatherStackResponse

{

[JsonPropertyName("current")]

public Current CurrentWeather { get; set; }

public class Current

{

[JsonPropertyName("temperature")]

public int Temperature { get; set; }

[JsonPropertyName("weather_descriptions")]

public string[] WeatherDescriptions { get; set; }

[JsonPropertyName("wind_speed")]

public int WindSpeed { get; set; }

[JsonPropertyName("pressure")]

public int Pressure { get; set; }

[JsonPropertyName("humidity")]

public int Humidity { get; set; }

[JsonPropertyName("feelslike")]

public int FeelsLike { get; set; }

}

}

}

Notice that I used JsonPropertyName attribute to identify what JSON property is each property matching. Here is the structure that we are going to map.

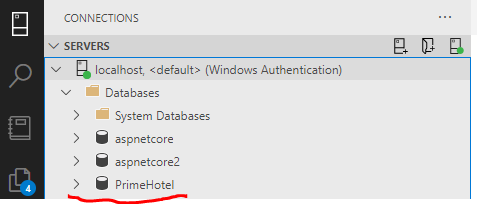

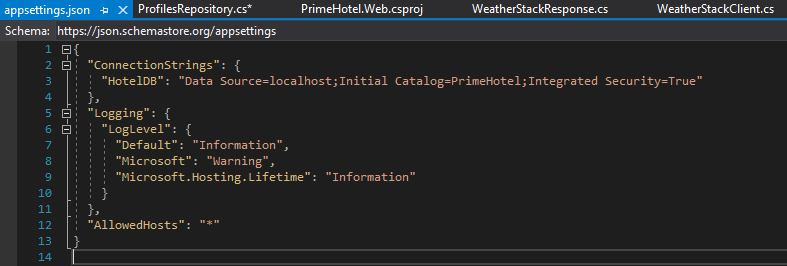

One last thing – we need to register our WeatherStackClient in a Dependency Injection container. In order to do so, we need to go to Startup class and add the following line in ConfigureServices method.

services.AddHttpClient<IWeatherStackClient, WeatherStackClient>();

We are using a dedicated method for registering classes using HttpClient. Underneath it’s using IHttpClientFactory that helps to maintain the pooling and lifetime of clients. You have a limited number of HTTP connections that you can maintain on your machine and if you create too much clients each blocking a connection, you will end up failing some of your requests. It also adds a configurable logging experience (via ILogger) for all requests sent through. All in all, it makes a developer’s life easier and allows you to do some smart stuff too.

Does it work? Yes it does! The response was correctly mapped into my class and I can return it.

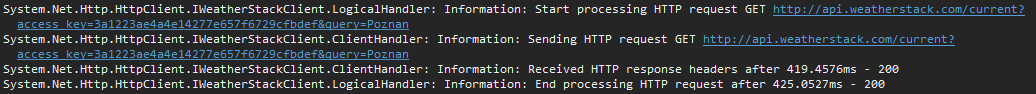

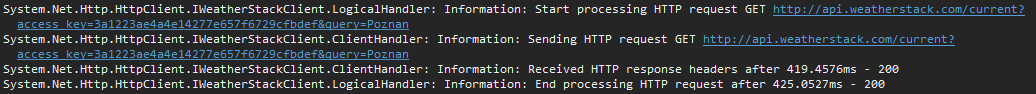

Do you wonder what was logged when making this request? Let’s have a quick look.

As I mentioned earlier IHttpClientFactory also provides a logging mechanism, so that every request is logged. Here you can see that not only address was logged, but also HTTP method and time of execution. This can be pretty useful for debugging.

Adding a retry mechanism

In a micro-services world, every micro-service can have a bad day once in a while. Therefore, we need to have a retry mechanism for services we call and we know that they fail from time to time. In ASP.NET Core for .NET 5 there is a third-party library integrated just that purpose – it’s Polly. Polly is a comprehensive resilience and transient fault-handling library for .NET. It allows developers to express policies such as Retry, Circuit Breaker, Timeout, Bulkhead Isolation, and Fallback in a fluent and thread-safe manner.

For our scenario let’s add a retry mechanism, that will call WeatherStack service and retry 3 times after an initial failure. With Polly, a number of retries and delays between then can be easily set. Let’s have a look at the example – it’s in the Startup method where we configure DI container.

services.AddHttpClient<IWeatherStackClient, WeatherStackClient>()

.AddTransientHttpErrorPolicy(

p => p.WaitAndRetryAsync(new[]

{

TimeSpan.FromSeconds(1),

TimeSpan.FromSeconds(5),

TimeSpan.FromSeconds(10)

}));

With this code we will retry the same request after 1, 5, and 10 seconds delay. There is no additional code needed. Polly will do everything for us. We will see logs that something failed, only after all retries will fail, we will get the exception.

Adding a cancellation token

A cancellation token is a mechanism that can stop the execution of an async call. Let’s say that our request shouldn’t take more than 3 seconds, because if it does, we know that something isn’t right and there is no point to wait.

To implement that we need to create a cancellation token and provide that when making a call with an HTTP client.

public async Task<WeatherStackResponse> GetCurrentWeatherWithAuth(string city)

{

try

{

using var cancellationTokenSource = new CancellationTokenSource(TimeSpan.FromSeconds(3));

using var responseStream = await _client.GetStreamAsync(GetWeatherStackUrl(city), cancellationTokenSource.Token);

var currentForecast = await JsonSerializer.DeserializeAsync<WeatherStackResponse>(responseStream);

return currentForecast;

}

catch (TaskCanceledException ec)

{

_logger.LogError(ec, $"Call to WeatherStack.com took longer then 3 seconds and had timed out ");

return null;

}

catch (Exception e)

{

_logger.LogError(e, $"Something went wrong when calling WeatherStack.com");

return null;

}

}

If the request takes too long, we will receive a TaskCancelledException, which we can catch and react to it differently, that when getting unexpected exception.

Provide authorization

Basic authorization is definitely the simplest and one of the most popular ones used. The idea is that every request to the specific service needs to be authorized, so that along with our content, we need to send authorization info. With basic authorization, we need to pass a user and password encoded as base64 string and put in a request header. Let’s see how that can be accomplished.

private const string ApiKey = "3a1223ae4a4e14277e657f6729cfbdef";

private const string Username = "Mik";

private const string Password = "****";

public WeatherStackClient(HttpClient client, ILogger<WeatherStackClient> logger)

{

_client = client;

_logger = logger;

var authToken = Encoding.ASCII.GetBytes($"{Username}:{Password}");

_client.DefaultRequestHeaders.Authorization = new AuthenticationHeaderValue(

"Basic",

Convert.ToBase64String(authToken));

}

In this way every call from WeatherStackClient will have authorization info and we do not need to add anything when we make requests. The only place we need to put additional code is a constructor.

Note that authorization is not needed to call weatherstack.com and is added only to show how it can be done.

This article did not cover all of the possibilities of IHttpClientFactory so if you want to know more, just go to this Microsoft article.

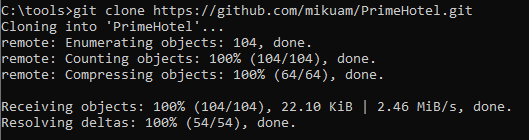

Hope you like this post, all code posted in this article is available at my GitHub account:

https://github.com/mikuam/PrimeHotel